On March 10, 1985 after getting back from Tijuana, México we got ready for the reception of the 5th North American Mushroom Conference in San Diego, California

See below post about previous posts.

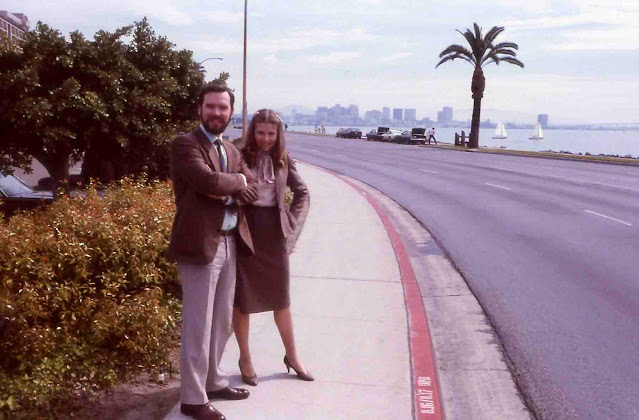

Reception where we met Pieter's Campbell Soup colleague Aron Kinrus (l) and his wife Shyfra (r).

The couple where both of us stayed for a couple of weeks before our Exodus from Pennsylvania, USA...

See post below.

Aron took this picture from the three of us...

On March 12 lectures about CROP MANAGEMENT

Pieter presented at 11:10 till 11:30—CROP MANAGEMENT FROM CASE HOLD TO FIRST BREAK

Pieter did very well and got lots of applaus and there were many in the audience.

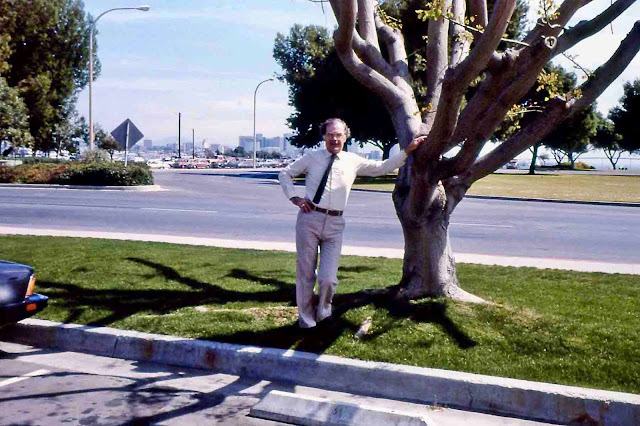

Pieter to the left before being introduced as the next speaker by Jim Yeatman.

Jim Yeatman did visit us in Dublin, Georgia on August 10 the next year, with someone from South Africa, see post below.

Always a very interesting schedule...

On March 12 we woud end the day with DINNER AND DANCE in the Grand Ballroom

SPEAKERS & PARTICIPANTS

CONFERENCE SPONSORS

Feeling relaxed after Pieter's presentation and enjoying the Dinner–Dance

Lots of glare and even Pieter's suit got totally affected...

Again lots of glare...

But Pieter sure felt happy and relaxed after having given his presentation in the morning...

Grateful to Chairman Geoff Price for providing us with this Mushroom News September 1985 publication!

Thank you letter to Pieter:

Your presentation, "Crop Management From Case Hold to First Break," was well received and certainly contributed to the success of the conference. Your personal time and effort in preparing your talk were evident and appreciated by the committee.

Again, thank you for your contribution.

Sincerely,

Edward A. Leo

Vice Chairman, 5th NAMC

~

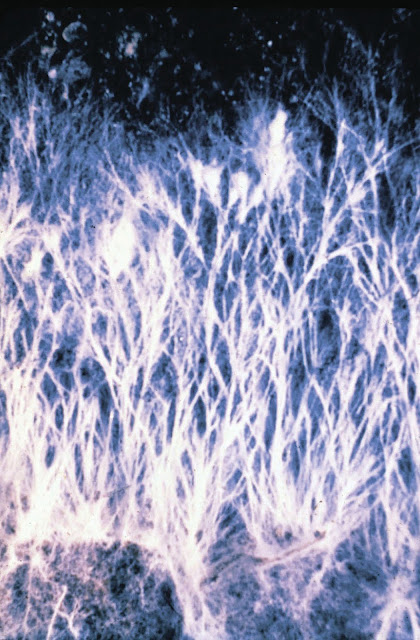

Casing to First Break

Pieter J.C. Vedder, Camsco (Campbell Soup) Produce Co., Dudley, Georgia

Presented at the 5th N.A.M.C. in San Diego.

In a short time I just can give you some ideas about what I think is important to reach the goal (not an easy goal) of a high yield with a good quality. Whatever growing system you have, what we all need first at the moment of casing is a good full grown compost with a moisture content of 63–66%, a pH of around 6.5 and a total nitrogen of let's say 2.2%. Because of the variation in ash content we maybe better talk about a C/N ratio of about 16 at spawning.

The plastic which was protecting the surface of the compost during spawn run from drying out and from contamination, has to be removed one or two days prior to casing to give the condensation water the opportunity to disappear.

Green molds on the surface are a sign that the compost is not selective enough, they show us that there are more easily degradable carbohydrates available because of an improper Phase I and/or Phase II, or we brought them in with the spawn grains or supplement. For that reason I don't like a heavy surface spawning; that means more as 10%. In spite of the development of different so–called slow release supplements, I prefer supplementing at spawning (if possible, of course). It is also much easier to manage the compost temperature if there is a wet casing layer on top, because we can create evaporation, which means cooling. We know that the best protection against competitor molds is a strong antagonism, buit up by the mushroom mycelium during a vigorous spawn run. I suppose that for the same reason we will have less problems with nematodes, molds, etc. and the yield will be higher after a 14 day spawn run as compared with e.g. 10 or 11 days.

I prefer a not too fluffy, somewhat heavy, casing material with a certain "body," because that has, in my opinion, a positive effect on the quality of the mushrooms. Very important also is that the material has a good water holding capacity. A mixture of not too fine peat moss and e.g. 20–25% spent lime, a by–product of the sugar industry, gives nice casing material. We prefer a pH in the 7.2–7.3 range for our casing material. It is much easier to maintain the right, high moisture content if the casing layer has a depth of at least 1 ½ inch (3.8 cm) or even better 1 ¾ of an inch (4.5 cm).

To produce a good quality mushroom with a better shelf life and also to avoid blotch, etc., we don't like to water the beds for a certain period of time prior to harvesting. That means that we need a moisture reserve in the casing layer, especially for a heavy first break. Growers often talk about the need for material with a better water holding capacity. The easiest way to increase the water holding capacity is to make the casing layer somewhat thicker. (This will change maybe with the new synthetic polymers recently available on the market).

Although it is known that the mushrooms take most of the water out of the compost, a firm casing layer with a good water holding capacity is very important.

In my opinion, in most of the cases the disadvantages of steaming the casing material are still bigger than the advantages. Steaming makes the casing material more sensitive for a new contamination; is affecting the water holding capacity and structure negatively and cost a lot of money on top of that. If the casing material is heavily contaminated with bubble, nematodes, or something like that, we should search for another source or revise the farm hygiene. With a good sanitation program and a vigorous spawn run there is most times no need for this costly technique.

The consequence of filling the trays or beds with fully grown compost or supplementing at casing is that we disturb and damage the mycelium in the compost. We have to give the mycelium some time to recover and re–colonize the compost surface, so better we don't water heavily just after casing. I prefer therefore a casing material with a moisture content of at east 75% or even more. (Of course if we are able to handle such a wet material).

The objective for the first couple of days after casing is to get a good inter–connecting mycelial growth between the compost and casing. As long as the casing material is not really saturated we have to water the beds several times in the days after casing. It is very important however that excessive water is not added which will run through the casing and rest on top of the compost, thereby causing a delay in mycelial growth and creating a somewhat greasy layer ideal for e.g. nematodes. This is possibly the main reason for a well wetted material at the time of application to the beds.

A somewhat sealed surface the first week after casing seems to be preferable. A high level of metabolics, produced by the growing mycelium, seems to stimulate the micro–organisms in the casing layer, which have a positive effect on fructification. After casing, we should manage the air temperature that way that the main part of the compost and casing material is in the 76–80°F (24.4–26.6°C) area. For the vegetative stage, we prefer a high relative humidity and also a high carbon dioxide concentration; high means above 3000–4000 PPM or even higher. Ventilation, that means supplying fresh air, is therefore only necessary if the compost temperature is rising too high.

This sometimes creates a problem. If the temperature, for whatever reason, is rising too high 6–7 days after casing, one has to open the vents to bring the bed temperature in line. This however often is initiating fructification rather deep in the casing layer. If we flush again, then we initiate a second layer of pins over the deeper formed first layer, thus the so–called double pinning. To avoid this problem we should have the opportunity for internal cooling without using fresh air. What we can do if we do not have that possibility is cool down the beds till e.g. 70°F (21°C) at day 5–6 so that we have some extra time to keep the room closed prior to flushing.

Very important in relation to this problem is a good selective compost and spawn run of at least 14–15 days. For this reason, it possibly will be better to stay away from supplementing during the summer. High temperature spots are normally not the result of the growth of the mushroom mycelium but are most times showing the activity of competitor molds, indicating a lack of selectivity as the result of an improper Phase I and Phase II.

We all are looking for a good first break, say around 2.5–3.0 lbs per square foot, and at the same time, a good quality mushroom. You can only have this if the mushrooms are spread very even over the bed surface; no clumps, or heavy clusters and no bare spots. With traditional casing methods, the arrival of the mycelium at the surface 6–7 days after casing tends to be uneven, and a compromise between advanced and backward parts must be reached. Shallow patches will show mycelium at the surface well in advance of deep areas.

In relation to this problem, we have good experience with the deep scratching or ruffling technique. As soon as the mycelium has developed about three quarters of the way into the casing layer, which is most times the case 5–7 days after casing, we mix in the mycelium and by doing so, simultaneously break up the surface compaction. An equal distribution of mycelium throughout the casing layer ensures that all mycelium at the bed surface is at the same stage of development. As a result, competition among mushroom initials is equalized, allowing even development without clumping or under pinning.

We have to realize that deep scratching or ruffling cannot compensate for an uneven compost and/or casing layer. Lack of evenness at the bed surface is most times created at filling or spawning. Patching or dust–covering is in my opinion not a good solution for this problem.

The modern shelf beds with metal side boards give of course the best opportunity for leveling and deep scratching and as the result of that, an even break. Even watering can be mechanized then.

After scratching, we have to give the mycelium the opportunity to restore and come up to the surface of the casing layer. To reach that goal, we maintain the optimum climate for the vegetative growth, so high CO₂ level, high relative humidity, and temperature in the mid 70's (24°C) for another 24 or more hours.

Fructification is the result of a combination of different factors as there are; temperature, CO₂–concentration, relative humidity (that means evaporation rate), micro–organisms, etc.

To ensure the occurrence of clean mushrooms, initiating of fruit bodies should occur on or near the surface of the casing layer. The flushing technique depends not only on the strain, but also on the ability to control the environment. With the strain we grow, we prefer a somewhat soft flush.

We don't like over pinning, 66 pieces per pound instead of 30, but on the other hand, to get the necessary quantity in the first break, let's say between 2.5 and 3.0 lbs., we need a certain number of fruit bodies. As a rule of thumb, we can say that lower temperatures and lower CO₂ concentrations give more fruit bodies. Stroma is most times the result of high CO₂ concentrations, high relative humidity, and too late flushing.

Related links: